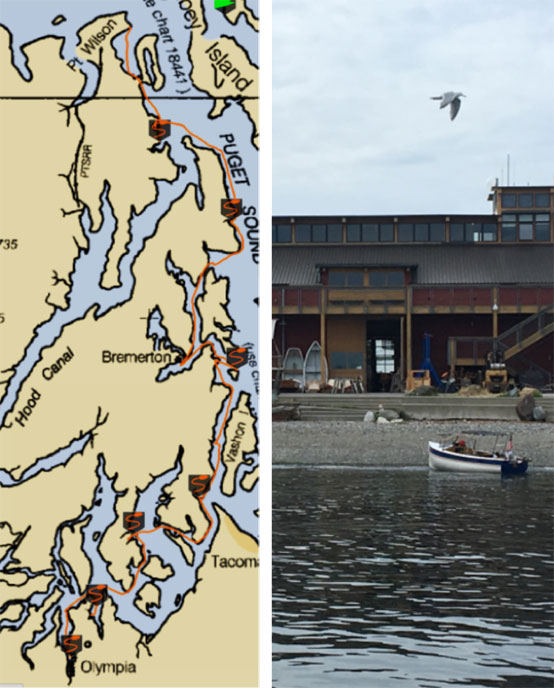

According to Desmond's book Electric Boats and Ships, in 1981, a year after I graduated from high school, Max Schick, a Swiss solar developer captained his solar boat 134 nautical miles on Swiss lakes over a one week period. I just completed a one week trip with a bunch of sailors up the Salish Sea traveling 120 nautical miles in the same time period. Eisenhower said there's nothing new but the history we forgot. True, so true.

Schick's boat could not handle the same seas, and while his solar cells were bleeding edge at the time and not available to the public, mine came from Amazon at the last minute. My EP Carry is a standard product available to anyone, I used a boat in the back yard instead of making a custom demo craft, and I traveled with an organized group of pocket yachters on a week's vacation, not as a supported researcher. In 1980 we thought we'd have unlimited energy and matter transporters by now – not true. The good news is that in 2019, I did, at least, duplicate Schick's voyage, but this time on a budget, with more comfort, with store-bought materials, and in much harsher conditions. That means today, anybody can do this, and much more.

Swe’Pea looks like a powerboat but she's not. She's a solar sailor. I am often asked how far you can go on solar. Well, just like sailing, when you're traveling on harvested energy in real time, your results can vary. So how far can you go on the wind? Answer depends on the tides, wind, speed… and it's similar with solar sailing. So the short answer is “Equal to your auxiliary range”. The long answer is what this article is all about.

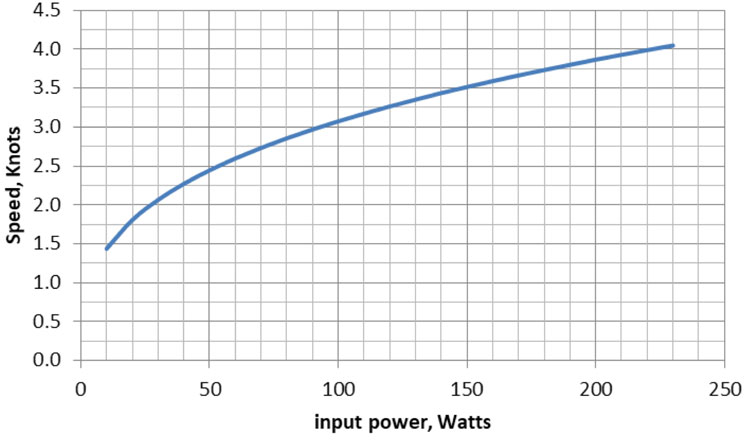

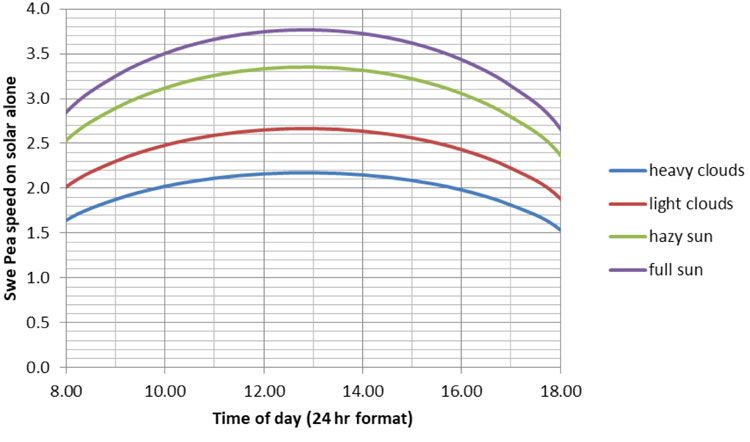

For example, on a cloudy day at 8:00 AM, Swe’Pea could generate enough power for 1.9 knots (the cloud's terms). This is half throttle — which takes discipline to remain at when there is reserve/extra power stored in an onboard battery. But at full throttle (4 knots), solar collection extends my 1-hour battery runtime by only 4 minutes. In other words, you need to accept the sun just as a sailor accepts the wind. Use what's given, or it's just another electric boat with a fancy expensive roof.

Not to say that you can't rely on the sun. With just 20% of Swe’Pea's footprint collecting very dark and cloudy solar watts, she went over 13 nm ending with a full charge on her tiny EP Carry battery. She also did this in lock step with similarly sized sailboats. So in fact, you can rely on the sun — it's just on the cloud's terms.

Personally, I am sold on solar sailing. This was a very comfortable, engaging and effective way to see the Salish. I kept a spare EP Carry battery stored away in case of trouble- it was not used. I was never at less than 44% charge and at no time did I feel nervous about range. The sun varied in intensity throughout each day's cloud cover but it was always enough for forward progress, even if the battery was depleted and if clouds were heavy.

This was really fun! I hope you try it too. It's accessible and if you're a sailor at heart, I'm sure you'll like it too.

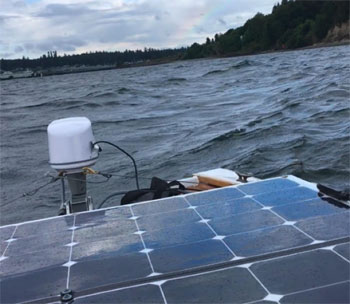

This is my experience on the Salish 100 going all solar on a 13-foot dinghy using a standard EP Carry and it's little 6 lb battery. The battery was recharged in real-time by a 200-watt solar array.

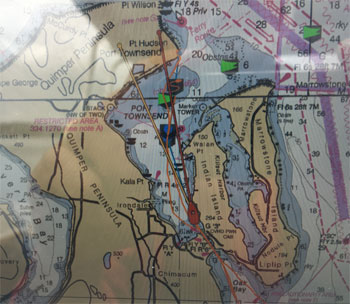

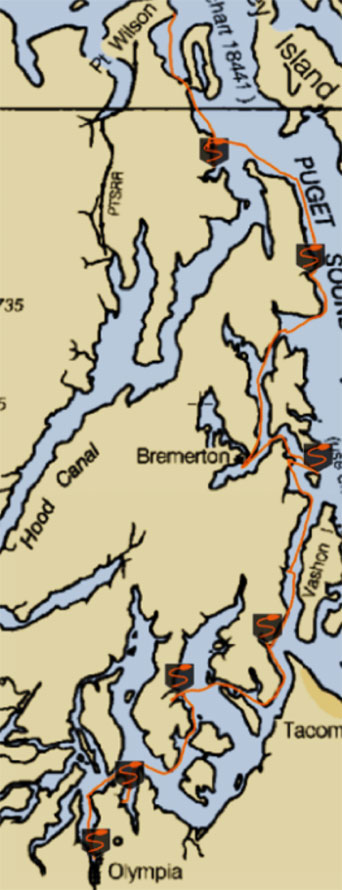

The Salish 100 is a week-long cruise, 100 nautical miles up the length of the Salish Sea (Puget Sound) from Olympia to Port Townsend. Spring in the Salish- weather was constantly changing. We timed each day with the tides as any sailor should, we saw 25 knot winds with 2 ft chop on the nose, we traveled in 3 ft following steep seas and hit the respectable rips on Point-No-Point. We also had long stretches of calm and we all made new friends. Both Swe’Pea and her solar powered EP Carry system worked flawlessly.

I designed the EP Carry to replace small gasoline outboards for good. It has world-class efficiency with its brushless motor, and lithium battery. But in development, I also wanted to address what no outboard manufacturer yet done; focus on the entire ownership experience. That includes actual boat speeds, boat trim, motor and battery handling, transport, storage, charging, robust plug and play connections, more safety features, ½ the weight, great appearance, no maintenance, impact survivability, corrosion prevention, ergonomics, maneuvering, security, entanglement, and beaching ease.

We illustrate all these usability elements on our website. And users agree that this little EP Carry is the easiest to use and easiest to own motor ever. But we still needed to demonstrate the relevance of our incredible efficiency.

Electric dinghies typically need to be supported by the mothership. Using less electricity lowers the impact of charging on the house system to a point where literally any mothership can charge the EP Carry's battery without running a generator or the auxiliary. You can even recharge the EP Carry's battery one time each day with a 40 watt solar panel, small enough to fit on the seat of a dinghy. But I wanted to drive the point home on how small a solar array needs to be for continuous distance travel using the EP Carry, and I wanted to demonstrate ho0w I rely on the EP Carry even in tough headwinds, continuous running, impacts with debris and groundings, pretty impressive tide rips and lots of salt exposure.

So I decided to put a little skin in the game and commit the motor (production serial No. 6) to a publicized 100-mile springtime cruise from Olympia to Port Townsend — the length of the Salish Sea (Roughly, Salish Sea includes Georgia Strait, Puget Sound, and Strait of Juan de Fuca). If the motor or solar scheme failed, everybody would see. The Salish 100 was an ideal trip to demonstrate the value of our efficiency, and to show how reliable the system is in all conditions.

In one day, our 13-foot dinghy traveled 26.2 nautical miles on a solar array covering just 20% of Swe’Pea's footprint. And I ended that day with a higher battery charge level than at the start even with rough seas and stormy conditions at the end. Using a trolling motor, I would have required four times the solar array size – so efficiency is important. I could not have done this trip without our little EP Carry.

We recommend the EP Carry for boats up to 13 ft and 600 lb and this was our loaded state for the trip. We outfitted Swe Pea, our 13-foot wooden dinghy, with a solar pop-top, charge controller, meters, safety and navigation equipment. I outfitted myself with warm waterproof clothing, food, water, a port-a-potty, sleeping pads, tent, pads, cooking things.

Boat: Total dry weight approx. 300 lb. A 1950s hot-molded mahogany jet-14 hull shortened by 1 ft to remove rotted sections, 1-1/2” fir transom and motor well. Shear was raised by 8 inches and a new deck and windshield added in 2001. Forward and aft bench seating. Her photo below shows her with her first electric motor, a converted 2-stroke gasoline unit weighing 40 lb with 140 lb of batteries. She's since gone on quite a diet with her 20 lb EP Carry/battery system.

Motor and battery: Total weight 20.4 lb. From the standard EP Carry system package. I kept a second battery stored onboard for emergency use, but never needed it. The motor was modified for remote steering and throttle control but otherwise it was standard issue. This resulted in the loss of the handy “tiller-pull” raising feature. So beaching, like any other motor, was a pain. Note: Use a high-efficiency motor like EP Carry if you can carry 200 watts (12.3 square ft.) of panels.

Solar panels: (shown in lowered position) 2 ALLPOWERS Solar Panel 100W 18V 12V wired in series. Total weight 16 lb. There are many brands of semi-flex panels using Sunpower cells. This is just the one I happened to purchase because it had the least non-active surface around the edges. These panels are recommended after this trip- good efficiency, no hiccups. Panels were fashioned into a pop-top to act as a rigid Bimini up and away from shadows. It could also be lowered for windage reduction, heavy seas and when trailering. Each panel measures 21” x 42” so the array is 42” x 42” in my arrangement. The panels therefore cover 12.25 square feet. With the pop top up, I was shielded from the sun, and to the rain to some extent.

Solar controller: The EP Carry battery will self-regulate its charge with a direct connection to solar panels under 100 watts but I was using 200 watts of panels so I needed a charge controller; a GreeSonic MPPT Solar Charge Controller 15A 12V/ 24V Waterproof (MPPT1575). I set Swe-Pea's solar system last minute without enough time to obtain the desired controller. But the GreeSonic was available and supposed to be programmable for Lithium charge needs. However, re-programming is not yet possible as it turns out, so this MPPT is not recommended for this application; Stuck with lead acid battery output parameters, the GreeSonic goes to a reduced current mode (float) at voltages corresponding to a state of charge of only 85% - 90% for the lithium battery. So it was best to run the battery down to below 85% state of charge immediately to maximize the solar current into the battery and motor. It however is able to manage the battery charging safely, and to 100% eventually. For this trip, I would recommend instead the Genasun GV-Boost solar charge controller with MPPT for 24V Lithium Batteries, though I have not tested it.

House electronics: A K2 12v battery provided house power during the trip. It had its own 35 watt panel. K2 batteries provide their own internal charge control that opens the internal battery circuit when the battery reaches balance and 100% state of charge. That means that when fully charged, the terminals go to the solar panel VOC which might damage electronics. So I was careful to not let the VOC condition occur for my house bank. Electronics were minimal– a depth sounder, bilge pump, nav lights, and a USB charge port for charging the nav tablet, phone and VHF radio.

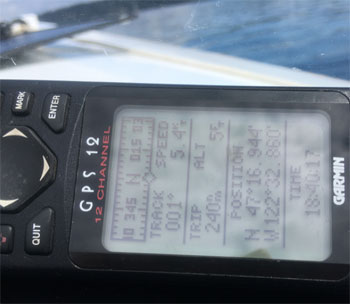

Meters: On a trip like this, you need to see what's happening to control it properly. There are two critical bits of info needed; power into or out of the battery, and the state of charge in the battery. Everything else is extra info to support geekdom. I used a $45 LCD screen coulomb counter meter (Battery Coulometer TK15) arranged to show the battery's state of charge and charge/discharge rate. It is not robust physically but with care, it worked flawlessly on this trip. This product is recommended if it can be adequately protected from the weather and handling. Other options are to use an ammeter that can show positive and reverse current flow, and a good state of charge meter. Note that unlike with lead acid batteries, voltage meters are not effective or accurate on lithium batteries unless readings are taken in fixed conditions. A true coulomb meter is needed for Lithium.

Safety: Here's the list: (total weight 60 lb)

Weights (in lb)

665 Total weight (lb)

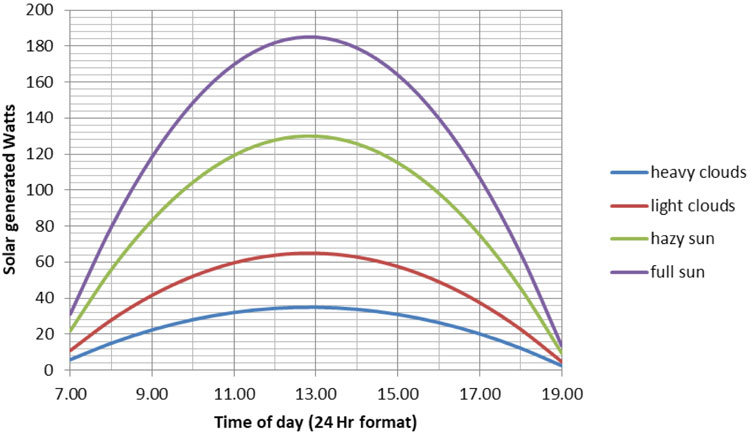

Power generated.Note this is for the actual panels and conditions as used on my trip. It is a measure of actual performance so this would include both the flat orientation of my panels, and the natural sunlight intensity changes by inclination.

Note that the difference between heavy and light clouds is 38 W vs 64 W and even on heavy overcast days, output varies depending on the thickness of the clouds at that particular time. In full sun, power is almost 5x that under dark skies. So you need to keep on the controls every few minutes to keep up. Just like tending a sail, the throttle needs tending.

Here's how cloudy mornings started: At 8:00 AM I could generate 15 watts under very heavy cloud cover. For 2 knots of speed, I needed only 25 watts into the motor so that's 10 Watts from the battery. Keeping that throttle setting, battery draw would diminish to zero by 9:00 AM when I was collecting all 25 watts from the clouds.

In reality, cloud cover was always changing and I found that 2.5 knots right away was a good choice, relying on the fact that higher collection points would happen later in the day. Even on cloudy days, I ended up at 40-50 Watts (2.5 knots over the water) into the motor mid-day while still charging the battery to overcome the morning deficit. On sunny days the picture was much better as you can see in my log later in this report.

This chart combines the solar availability chart above, and Swe’Pea's speed-power curve above. If I were to use the battery, Swe’Pea's speed was 4 knots over the water. In reality, due to good planning on the Salish 100 planning folks, we saw an average tidal lift except for those days I went rogue to visit places and friends from my childhood.

If it's a full sunny day and you travel from 8:00 AM to 6:00 PM using no battery, you can go over 40 miles. That distance is down to 23 miles on a consistently cloudy day.

Every day saw varying conditions. Days would often start with heavy overcast, and switch through all conditions to full-sun and then back to heavy clouds when we saw most of the rain in the afternoon. It requires attending the coulomb meter to assess both the state of charge and charge/ discharge rate to track actual sun-generated power.

On average Swe’Pea did 3.2 knots over the ground each day- some days less if they were mostly overcast and some more if mostly sunny.

Interesting note: It seems that the solar motor arrangement is a good auxiliary option for sailboats; Swe’Pea tended to have more favorable power-generation on the days with little wind. On windy days, the sailboats would outrun me like what happened when we rounded Point-No-Point. So sailing and solar seem to fit well together.

Heavy overcast day. Swe’Pea started with a full charge on the 6.4 lb. battery, enough juice to go only 6 nm. But with solar, she went twice that distance at an average speed of 3.2 knots and with a 76% state of charge at the end. She collected almost 2 battery chargings in these cloudy overcast conditions, exactly as I predicted. With variable winds, Swe’Pea did well in the company of pocket cruising sailboats.

Cloudy day. Started with an 76% state of charge from previous day. Maintained a high state of charge until the end of the day after speeding up for fun and then some last minute towing into Penrose harbor. Ended with only 65% at the end of the traveling day but charged significantly thereafter at the dock.

Visited a good friend and survived the raccoon-apocalypse.